Gender Distribution of Authors in Music Psychology

gender, transparency, music psychology, open science, meta-research

Introduction

In recent years, meta-scientific attention has increasingly turned toward music psychology, with a focus on how WEIRD (Jakubowski et al., 2025) and transparent (Eerola, 2024) the discipline is. In this study, we examine gender equality in authorship as an indicator of how equitably gender is represented within the field. Disparities in gender distribution may signal structural barriers and disciplinary cultures that constrain the diversity of contributors and hinder optimal knowledge production (Ni et al., 2021). Authorship visibility is also critical for academic career progression, influencing recognition, funding, and advancement opportunities. Establishing a clear understanding of gender representation in music psychology is therefore essential for supporting a more inclusive and sustainable academic community. Previous studies across various disciplines—including psychology—have consistently revealed persistent gender inequalities in authorship, though the extent of these disparities varies by field (González-Alvarez & Sos-Peña, 2020; Rock et al., 2021; Shah et al., 2021; Son & Bell, 2022).

Academia suffers various equity issues, impacting productivity, innovation, and job satisfaction in the workplace, which-in turn-hugely impact academic progress. One aspect of this inequity is gender. Women are more at a disadvantage than men, with evidence suggesting that women are less present in positions of power. For instance, in the UK in 2016-17, 24.6% of professors are women (Bhopal & Henderson, 2021) when compared to the 44% of all grades in the UK academia (Harris et al., 2025). A similar situation holds for Italy (24% female professors) (Filandri & Pasqua, 2021), and to some extent for the United States (14%) (Spoon et al., 2023). A pay gap between men and women in academia is also significant, (e.g., female-male wage ratio is 0.85 in 2020 in the United Kingdom) (Quadlin et al., 2023). In a “publish or perish” culture of science and academia (Kiai, 2019), one crucial aspect to focus on is authorship. The number and quality (e.g., journal reputation) of authorships an individual determines crucial career development such as grant funding and future (permanent) positions.

Research across several scientific disciplines that show that women tend to be less represented in authors compared to men (Banks et al., 2025; Son & Bell, 2022). Encouragingly, however, there is a general trend that the ratio of women to men in authorships is improving. From around 1960 to 2021, studies show a general improvement (González-Alvarez & Sos-Peña, 2020; Ioannidis et al., 2023; Jemielniak & Wilamowski, 2025). Yet there is evidence that this improvement is plateauing (Jemielniak & Wilamowski, 2025) and that although women are more likely to be first author, women are still generally unfairly underrepresented as the last author (Brück, 2023; González-Alvarez & Sos-Peña, 2020; Rock et al., 2021; Shah et al., 2021). There could be several reasons for such a disparity: despite efforts to give fair credit for author contributions (Ni et al., 2021), for example, using the Contributor Roles Taxonomy (CRediT) system, assigning authorship can be unclear. What counts as an authorship may differ between academic disciplines. Women are more likely to experience authorship disagreements, for example, when to decide authorship: women prefer to discuss in earlier stages, while men choose authorship at the final stage (Ni et al., 2021). Another reason for the gender gap could also come from parenthood and parental leave, which account for about ~40% of gender gap in career advancement (Nielsen et al., 2024). Importantly, there are strides to improving this, with opinion papers discussing way to improve receipt and reporting of intellectual credit (Banks et al., 2025) as well as creating equitable environments in academic science (Martı́nez-Menéndez et al., 2024).

-> to add bits about gender authorships and country/continent: - Ioannidis et al. (2023) : compared high-income vs. non-high income countries. Higher number of authors in high-income countires, where men out-numbered women more so in high-income, though uncertain gender assignment more common in non-high income. - Sánchez-Jiménez et al. (2024) : looked at relationship between human development index (HDI) and female authorships - Son & Bell (2022): high female representation in Africa, lowest in Latin America and Caribbean. - Brück (2023) : proportion of women author varied by country (9.1% in Austria, 0% in South Korea)

-> to add about topics/keywords/approaches/methods: - Brück (2023) : in an analysis of medical journals, research keyword varied by gender. For men, it was phase II-III trials, oncology, immunotherapy (etc..), while for women, it was more related to healthcare-related themes like patient involvement, insurance, quality-of-care, access. - Sebo et al. (2020) : women more liekly to publish qualitative studies compared to experimental and systematic review articles, perhaps as females demonstrate better relational skill involved in qualitative studies, like prolongeed relationships and emotional ties with research participants. Women were also more likely to publish in primary healthcare journals. - Ashmos Plowman & Smith (2011) : men are under-represented, but women are over-represented in qualitative studies. - Thelwall et al. (2019) : females more likely to use exploratory and qualitative rather than quantitative methods. Females more interested in cell biology and veterinary science compared to males, who prefer abstraction, patients, and power/control field - Vogel & Jurafsky (2012) : in computer science (computational linguistics), used XX to look at topics that female / male authors published on. Female more likely to publish on dialog, discourse, and sentiment, while men more likely to publish in formal semantic and finite state models.

As the topics, and approaches and methods attract differential interest from men and women, it is important to recognise that fields of scholarship and academic disciplines vary considerably in terms of gender distribution (Huang et al., 2020). For example, a large survey of authors by González-Alvarez & Sos-Peña (2020) showed that the hard sciences (N = 119,592) had the lowest prevalence of women (14.8%), whereas in the biological and social sciences (N = 262,122) the proportion was substantially higher (43.3%). In psychology, which is perhaps the closest benchmark for the present focus on music psychology, female authors accounted for 45.2% of the sample (N = 90,067).

To improve certain academic equity issues, it is worthwhile focusing on our discipline and to assess the equity in music psychology. The past efforts such as Anglada-Tort & Sanfilippo (2019) have already provided a snapshot a rough overview of the state of affairs with suggestions of future directions to improve the field. Eerola (2024) showcases how Open Science practices (e.g., preregistrations, sharing research materials, data, and analysis scripts) are relatively limited, and encourage authors in the field to start implementing such practices. Jakubowski et al. (2025) explores participant samples and musical stimuli used across a wide range of experiment to give an idea of how limited or generalizable the field is, which the view to see how – as a field – we need to diversify participant samples and stimuli to gain a more realistic understanding. In a similar way to these papers, the current paper aims to give a current overview of authorship and gender patterns in the field of music psychology.

Aims

Our aim is to find out what is the gender distribution in the specialist journals of music psychology. What is the proportion of different types of authorships (single, first, coauthors, and last authorships) for men and women in the published papers in the last 25 years? Are there specific trends in terms of countries of the affiliations, topics, or time?

Methods

Materials and analyses

We retrieved bibliographic information for all articles published between 2000 and June 2025 from five specialist journals, resulting in 3,373 unique articles: Musicae Scientiae (N = 639), Psychology of Music (N = 1,231), Music Perception (N = 675), Journal of New Music Research (N = 563), and Music & Science (N = 265). These journals have also been used in previous meta-science studies to characterise research practices in music psychology (Jakubowski et al., 2025). Author affiliations were extracted automatically and converted into country-level data. However, these were not manually verified for each entry, as affiliations are not always clearly matched to individual authors due to variations in reporting conventions, such as multiple or partial affiliations.

In total, the dataset included 9066 authors, of whom 5312 were unique. Author affiliations spanned 63 countries. We also extracted citation counts and Open Access status from Scopus. Information on joint first authorship was not available in the data.

Gender attribution was initially based on first names. We recognise that treating gender as a binary category is inherently problematic. Gender is a complex and multidimensional social construct. However, consistent with prior meta-science research on gender and authorship (González-Alvarez & Sos-Peña, 2020; Ni et al., 2021; Rock et al., 2021; Shah et al., 2021; Son & Bell, 2022; Wais, 2006) and that non-binary authorship generally is less than 0.1% (Son & Bell, 2022), we adopt a binary classification—male and female—for analytical purposes and assume that first names allow for a reasonable, though imperfect, attribution of gender. We used the genderize API (Wais, 2006), which predicts gender from first names and can be supplemented with country information derived from author affiliations to improve accuracy. This method resolved the gender of 89.3% of authors with a probability greater than 0.90. Only 89 names had a low attribution probability (< 0.55). Unattributed cases were then checked manually, resulting in 185 manual corrections. After this process, 32 names remained ambiguous and 27 were unknown—some likely due to data entry errors in Scopus (e.g. only initials or surnames). These 59 cases were excluded from the dataset. It is likely that the due to challenge of attributing gender accurately not all the gender attributions are correct. Although genderize.io has been shown to achieve 96.6% accuracy in a diverse multinational test database without using a country of origin information – 98% with the information included – it also underperforms (82% accuracy) in Asian names (VanHelene et al., 2024). However, the error rates of these processes have been previously been shown to be non-biased, i.e. showing similar number of mistakes for both genders (Sebo, 2021; VanHelene et al., 2024).

We carried out manual corrections of the gender attributions where we were familiar with the author or the database had the full first name coded with initials, or the second name used as the first name. This led to 53 corrections.

We defined four types of authorship positions: single authorship, first authorship (which does not include papers with a single author), coauthorship, and last authorship. Coauthorship includes all positions other than first and last. These positions carry different academic prestige: first authorship is typically associated with the primary contributor, while last authorship is often held by senior researchers with established reputations (Tscharntke et al., 2007).

For the analyses, we analysed gender disparities in authorship by comparing the frequency of these authorship types between male and female authors. Our analysis focused on the female author proportion (FAP) and odds ratios (ORs) comparing the likelihood of occupying each authorship position by gender.

Results

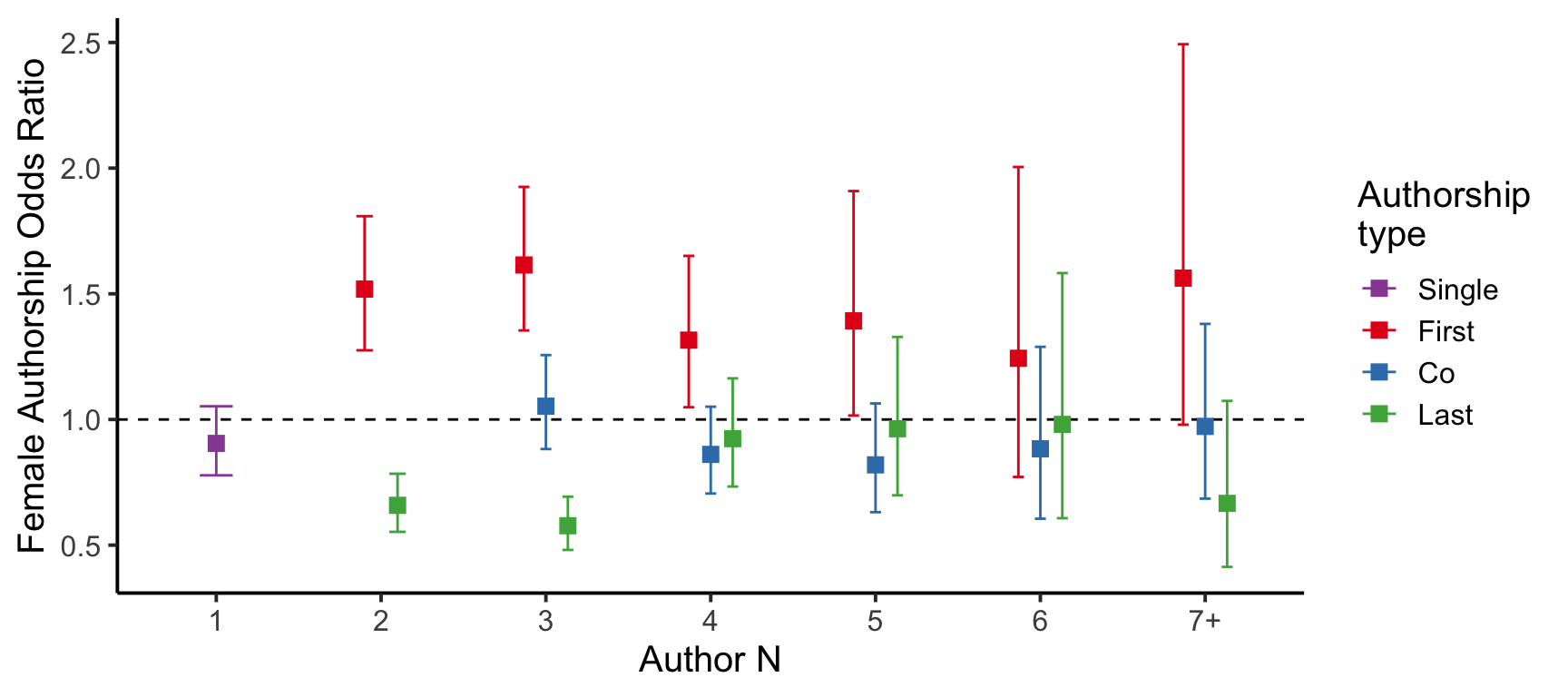

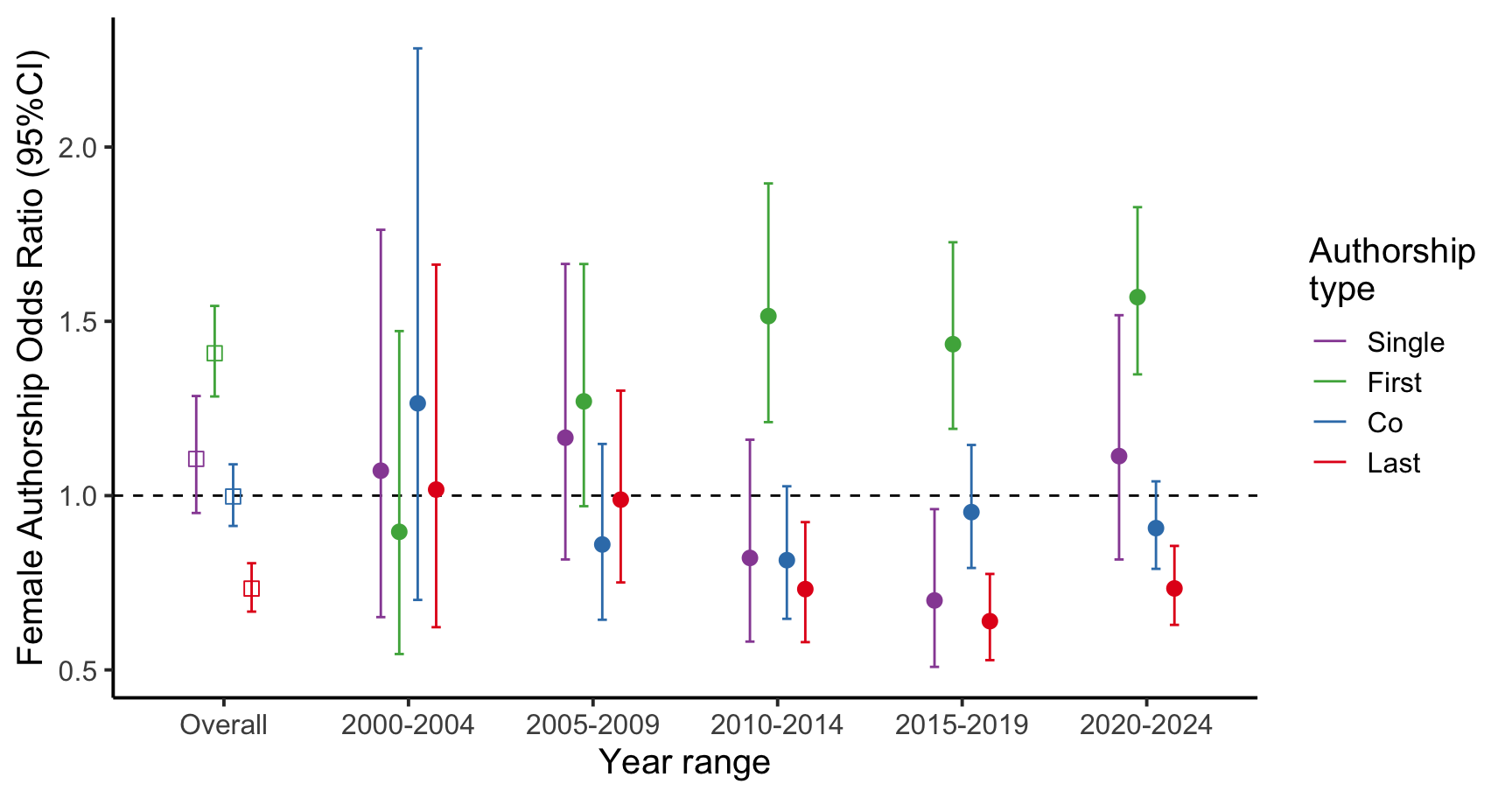

Among all authors (N = 9066), 40.2% (N = 3647) were identified as female. To account for the unequal number of male and female authors across the dataset, we used odds ratios (ORs) to compare the relative likelihood of females occupying different authorship positions. We first investigate the authorship types across gender and then examine the author order and the overall number of coauthors in more detail.

Citations and Open Access

One potential difference established in previous bibliometric analyses of gendered authorship is citations (Chatterjee & Werner, 2021; West et al., 2013). Here we tested whether the citations – as indexed by Scopus – show differences across gender. The median citation for studies with female lead authors is 10 [9–11], and for males, the numbers are identical (Md=10 [9–11]) and the difference is not statistically significant (\(\chi^2\)(1)=2.14, p = 0.144) using rank-based Wilcoxon test. The same comparison of citations for studies with last authors yields similar results 9.5 [8–11], and for males, the numbers are similar (Md=11 [10–12]). Again, the difference is not statistically significant (\(\chi^2\)(1)=2.04, p = 0.153). If we assume that we can weight in the gender contribution of all authors in a publication to its citation count, we observe a minor difference, where median citations for female authors is 9 [9–10], and for males, the central measure are statistically significantly higher (Md=10 [9–10], \(\chi^2\)(1)=16.05, p < 0.0001). For reference, prior study of citation patterns across gender in psychology has reported a small effect favoring men (M = 16.57) over women (M = 15.90) (González-Alvarez & Sos-Peña, 2020).

We also explored whether the open access status of the articles is associated with gender. Out of 3373 articles, 32.2% are Open Access in this sample, as indexed by Scopus. For first-authored articles, female odds ratio for Open Access is 1.49 [1.29–1.73], suggesting nearly 50% higher odds associated with publishing open access by women as compared to men. If we observe only the last authorship status of the publications, the difference vanishes with the odds ratio indisguishable from even division (1.00 and the confidence interval), OR = 0.86 [0.72–1.02].

Geographical differences

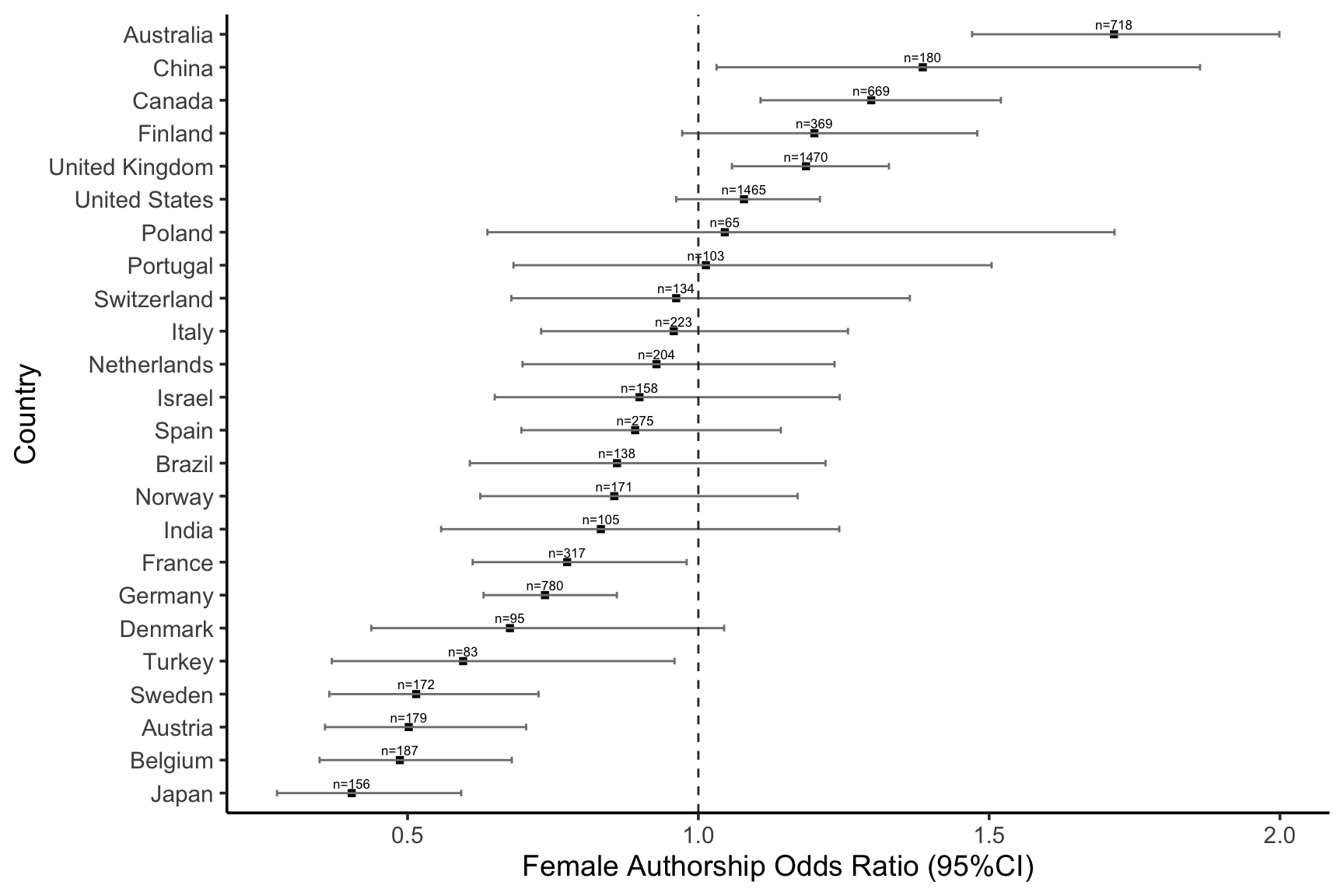

Past studies have identified consistent geographical patterns in female authorship. For example, a large-scale analysis of psychology publications found that 46.5% of authorships were by women, with European countries showing a lower average proportion of 42.8% (González-Alvarez & Sos-Peña, 2020). To examine geographical differences more closely, we calculated the odds of female authorship by the countries that have published at least 60 publications in the sample, as shown in Figure 3.

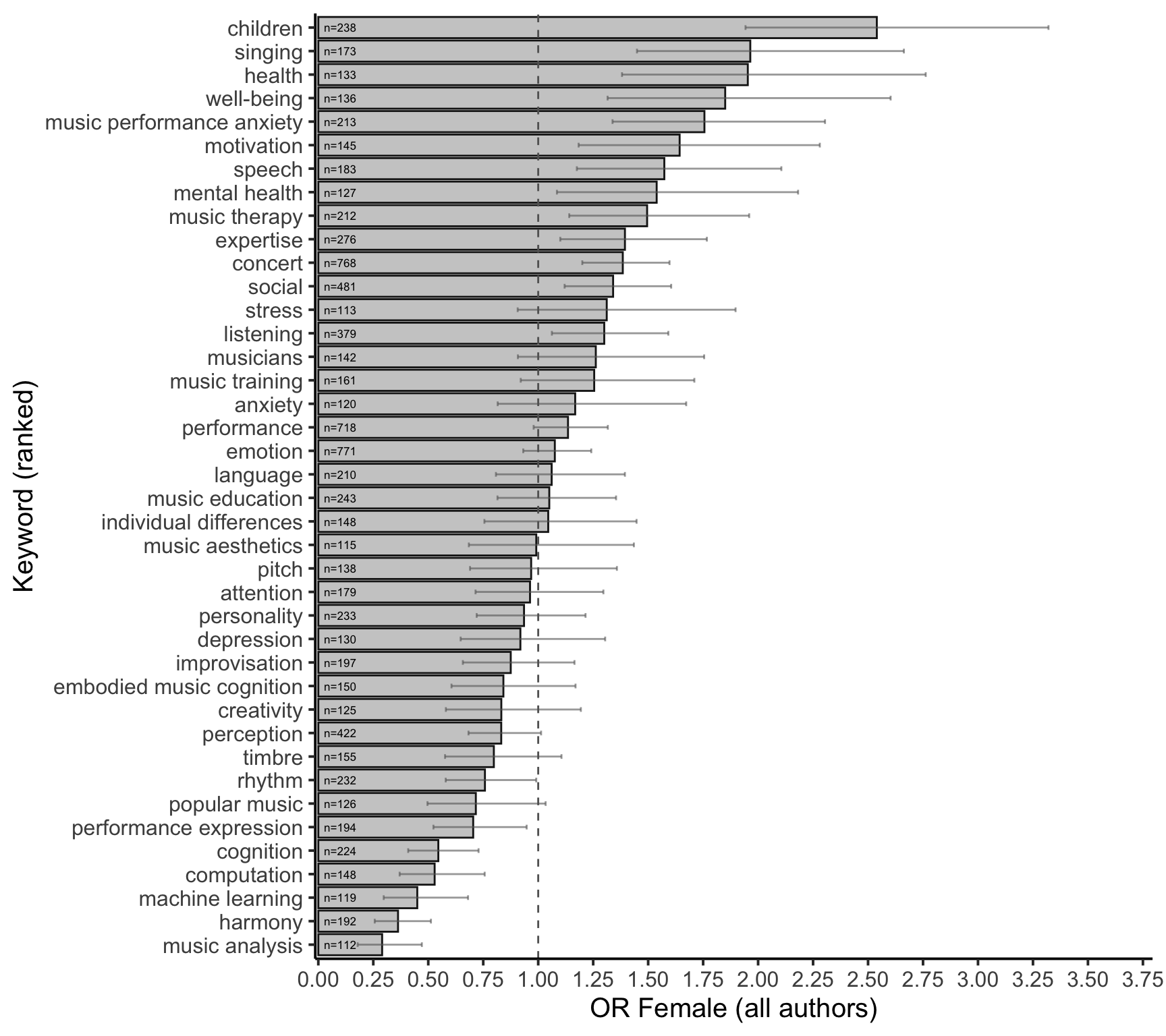

Gendered topics through analysis of keywords

To explore the potential differences within music psychology topics of choice between female and males, we analysed the keywords in the articles (15,316 in total, 6730 unique). To reduce variant keywords, we manually simplified the variants (e.g., “arts in health”, “healthy music use”, “health musicking” were converted to “music health” and “music cognition” to “cognition” and “music perception” to “perception”) and eliminated single use of the term “music”. We aggregated the counts of keywords across all authors in the articles and Figure 4 shows the odds ratios for female authors to be associated (in any author position) with the 40 most frequently used keywords. The keywords signifying related to children, development, emotion regulation, well-being, music performance anxiety, motivation, expertise, music listening, mental health, and music therapy show significantly higher odds ratios (OR \(\ge\) 1.50) for females in comparison to overall gender ratios in the data. At the opposite end of this continuum, topics such as music analysis, harmony, machine learning, computation, cognition, and performance expression show the opposite trend, suggesting that the articles with these keywords tend to have overall more prevalent male authorships (female OR \(\le\) 0.75).

Discussion

Authorship is a crucial aspect in academia as a marker of scholarly success and strongly influences academic career progression, influencing recognition, funding, and advancement opportunities. However, there are several inequities within this aspect of academia, with women often being underrepresented. As such representations differ across different disciplines, it is worthwhile to diagnose the situation in music psychology. The goal of the current paper was to provide a snapshot of authorship prevalence and roles across gender. While we recognise that gender is a complex and multidimensional social construct, and there are limitations to treating gender as a binary category, we used a binary male-female classification consistent with prior meta-science research on gender and authorship (González-Alvarez & Sos-Peña, 2020; Ni et al., 2021; Rock et al., 2021; Shah et al., 2021; Son & Bell, 2022; Wais, 2006).

In music psychology, the distribution of authors by gender remains unequal, with women representing 40.2% of authors. This proportion is higher than in musicology (34.8% (Eerola et al., in prep.)) and higher than in psychology more broadly, where women account for 33.2% of authors (Huang et al., 2020). In terms of authorship roles, notable differences emerge. Women are relatively more likely than men to appear as first authors, a trend that has become characteristic of the field only in the past 15 years. By contrast, women remain underrepresented in the last authorship position, and this trend has not changed substantially over the last 15 years. Given that last authorship in the social sciences is not universally defined but is increasingly associated with seniority, supervisory responsibility, or principal investigator status (Drivas, 2024), this underrepresentation suggests that women are less likely to occupy leadership roles such as lab heads or holders of substantial research resources. This pattern is consistent with broader evidence showing that women remain underrepresented in senior academic positions, including professorial appointments (Bakker & Jacobs, 2016), invitations to contribute to journals, and authorship in high-prestige outlets (Holman et al., 2018). Related analyses from science and medicine further show that women are more often associated with conducting experiments, whereas men are disproportionately represented in authorship roles linked to leadership and oversight (Macaluso et al., 2016).

There were substantial gender differences in citation patterns. One notable finding is that first-authored articles by women were significantly more likely to be published open access, with an odds ratio of 1.49, a result that warrants further exploration. This effect does not appear to be tied to specific journals. Although the odds ratio for women publishing open access is highest in Music and Science, the broader trend suggests a temporal shift: since around 2010, women have increasingly overtaken men in publishing open access. The data does not provide any reasons for this. While past surveys among UK academics have not indicated substantial differences in experiences with open access (Zhu, 2017), financial and other inequalities in emerging countries have been suggested to limit women’s capacity to publish in open access journals (Vuong et al., 2021).

Turning to potential drivers of these gender differences, geographical and cultural factors appear to play a major role. Our summaries of gender patterns across continents and countries indicate clear cross-national variation. Large Commonwealth nations, namely Australia, Canada, and the United Kingdom, seem to provide a cultural climate more supportive of women in research, as reflected in the relatively high odds ratios of women appearing as authors (in any authorship position) in music psychology. This pattern, however, is not universal across all countries examined (Chan & Torgler, 2020). Prior work shows that women’s research success is positively correlated with national indicators of gender equity (Chan & Torgler, 2020). This is likely to be related to a career length, which strongly correlates with overall productivity. Women exhibit higher dropout rates than men, particularly during the 5–10 years following their first publication (Huang et al., 2020), but policies geared towards equity and support for career breaks and caring responsibilities may well contribute towards the observed country-specific differences. Nevertheless, prior analyses demonstrate that even when women constitute a smaller share of researchers within a discipline or country, their contributions are often more impactful than those of their male colleagues (Chan & Torgler, 2020). When examining countries where women have significantly lower odds of authorship compared to men (Japan, Belgium, Austria, Sweden, and Turkey), it is not straightforward to conclude that these nations fall consistently at the lower end of gender equality rankings. The notable exception is Turkey, which is positioned lower according to the Gender Inequality Index (United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), 2025).

The keyword analysis of the articles indicated thematic differences in the topics studied by women and men. Research areas related to children, well-being, health, and mental health were more frequently associated with women. This pattern is consistent with observations in psychology more broadly, where women are more strongly represented in sub-disciplines that focus on care and nurturing (González-Alvarez & Sos-Peña, 2020). The higher likelihood of women studying topics related to singing may be connected to prevailing gender stereotypes, or to the early negative perceptions of singing among boys (Warzecha, 2013) and men (Palkki, 2015). In contrast, topics related to cognition and computation were more often associated with men, which reflects a wider trend in psychology (González-Alvarez & Sos-Peña, 2020).

Conclusions

The analysis of gender distributions in the five most prominent music psychology journals over the last 25 years presented a rich and evolving history of gender distribution in various authorship roles. While overall women hold smaller number of authorship overall (40.2%), they are more likely to hold first author positions in coauthored publications but less likely likely to hold last author positions than men. For solo publications and being a coauthor, there are no significant gender differences.

There was small but significant effect of gender on citations that favoured men when the citations were aggregated all authors in the papers. There was no, however, differences in citations for female first or last authors. The aggregated results are in line with previous findings in psychology that favored men (González-Alvarez & Sos-Peña, 2020). We also observed that female first authored articles tend to be more likely to be published as open access as male first authors. The past surveys of experiences and attitudes towards open access publishing has revealed gender differences typically in the opposite direction (Zhu, 2017).

While the present analysis cannot determine the underlying causes of the observed trends, we can point to several factors that may help explain why this discipline appears to be more equitably distributed by gender than, for example, psychology.

Female role models (past and present) exist in music psychology; many of the founding members of the societies have been women (e.g., Diana Deutsch and Edward Carterette for ICMPC in 1989, Irène Deliège for ESCOM in 1991), to a more recent ICMPC and ESCOM presidents? Editor-in-chiefs of the journals?).

Taking sub-disciplinary differences in psychology as an indicator of topic areas more often favoured by women, González-Alvarez & Sos-Peña (2020) observed that “nurturing” disciplines such as education and developmental psychology had higher proportions of female authors. In music psychology, however, a similar explanation may not apply. Keywords typically associated with nurturing domains (e.g., education, development, social, therapy, well-being, mental health, emotion regulation) account for only 17.9% of the total keyword counts among the top 40 keywords.

It would have been interesting to analyse the precarity of career options as judged from the years of authorship attributions (Lundine et al., 2018)

Current findings present a more optimistic outlook of female authors in comparison what the prevalence of female academics or professors in academia are (Bhopal & Henderson, 2021; Filandri & Pasqua, 2021; Harris et al., 2025). While we have comparable accounts from psychology, musicology and other disciplines of music research (popular music, ethnomusicology) tends to have less equal division gender; a recent analysis of the last 25 years of articles in 15 musicology journals amounting to 3,515 articles suggests that female authors are far more infrequent (34.8% [33.3%-36.3%]) than males (65.2% [63.7%-66.7%]) (Eerola et al., in prep.).

Senior/last authorship position and why such a large inbalance exists.

Funding statement

Authors received no funding for this research.

Competing interests statement

There were no competing interests.

Open practices statement

Study data, analysis scripts and supporting information is available at GitHub, https://tuomaseerola.github.io/gender_in_music_psych.